Goodbye to the Rainy

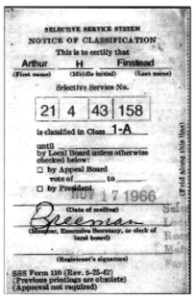

I am in good physical health and am classified 1-A by the Selective Service. Uncle Sam really does want me. In another week, I will board the bus for Fargo, North Dakota, and then to basic training, wherever that takes place, and then Vietnam! I still do not know if our country is doing the right thing; there are so many opinions out there. Right or wrong, I will see for myself. I see no other option. Canada, marriage, becoming a conscientious objector; none of these solutions have worked out. I know that I am naïve, but I still believe in our country, our government and I have the same old problem. I just cannot make up my mind and it is just easier to go with the flow. Jacob never tired of goading me to burn that card and be done with it and I could never tell if he was serious or not.

Comment: We were young and carefree college students in the early 60’s. Minnesota granted 2S, student deferments, to every male attending college classes full-time. Draft age married men, those with a dependent child, and those with a medical problem were also deferred. Bemidji State students paid little attention to the war being conducted in Vietnam. But as we advanced from that first year toward a four-year degree, the war continued to heat up as did our worries about the future. Classmates who dropped out of school were soon notified to report for basic training in the Army. Occasionally, over a casual conversation in the student lounge, someone would relate how a boy from their hometown had become a casualty of the war in Vietnam. The number of young men actually drafted continued to increase as President Johnson responded to General Westmorland’s call for more manpower.

In those college days, I was still a Republican. I was neither political nor interested in the military, and I still supported Nixon. (That is the Fenske birthright — Lutheran, Republican, a Fenske — not real sure in which order to list these labels.) Like most students, I was pretty indecisive. I checked with the local National Guard, but all of the openings had been spoken for. I visited a recruiter in the Twin Cities about a flight training program, but a high blood pressure reading ruled out that option (but it would be low enough to qualify as a ground soldier.) I even considered joining the Marine summer program for future officers in Quantico Virginia until a friend talked me down.

In my senior year, I decided that I would become a teacher and avoid that distant war. It was just a rumor, but the State might begin deferring math and science teachers. I checked my status with the local draft board secretary located in the Bemidji Federal Building. She was a very angry, unpleasant woman to talk with, but I realize now that she had been continually harassed by the many young men unhappy with a decision that she had nothing to do with—she was merely the messenger. She would give no guarantee that the deferment would be good for an out of state teaching position. I discussed my status with Bill, the local draft board chairman. He was a rah-rah guy who occasionally came out to lead the Carr Lake farmer’s Club members in song, and he had served in WWII. He advised that the Army would be “the best years of my life.” I received the “Greetings:” letter that I should report to the Markham Hotel, board the bus, and travel to Fargo, North Dakota for a pre-induction physical. We stopped at every small town between Bemidji and Fargo to pick up more potential soldiers. I passed and was reclassified as 1A.

My last quarter of school was student teaching in Park Rapids. Deciding to take a chance, I signed a contract to teach science with the Great Falls, Montana school system. Just before graduation, in a single week I received both my induction notice and a one-year deferment.

All of my teacher friends from North Dakota were given one year of teaching experience before they would be drafted. John and Jan from Minot played on a Great Falls softball team and one of their teammates was the Marine recruiter. He convinced them that the best solution to avoid the draft was to become a Marine officer. He ensured that they passed all of the qualifying tests. (John later was killed while leading a platoon in the jungles of Vietnam.)

I had to travel to Butte, Montana for another pre-induction physical. My Principal wrote a persuasive letter extolling my value to education and the Minnesota draft board granted me another year to teach science. Marilyn and I were married that summer and we made extensive plans as to our future of becoming long-term Montana residents. She unfortunately became very sick during the year with the complications of diabetes and eventually travelled by train to the University of Minnesota hospital for a full evaluation. They recommended care and treatment at the U so we made the decision to move back to Minnesota. I drove from Great Falls to Bemidji, then to Saint Francis for an interview, back to Bemidji, back to Great Falls, all on a three-day weekend.

Marilyn’s condition worsened (kidneys and eyesight) during that year at Saint Francis, but my draft board decided that three years was the maximum time they could grant a teaching deferment. They would draft me at the end of the teaching year. I applied for a medical hardship deferment and was required to have her two lead doctors write supporting letters. After months of worry and apprehension, the deferment was granted. Ironically, the draft lottery was instituted soon after and I was beyond that worry.

During that waiting period, Floyd, Marilyn’s father, reassured me that he, “would take me to Canada before those bastards got their hands on me.” Here is a story that is a “what if?” for that situation.

The Last Stand

The view seemed clear and we were in a hurry that June morning. The two of us stood in the early light and tried to absorb every piece of nature gilding the perimeter of our shared compass. We wanted it all. There were few words; words could not do justice to this magnificent land. The love of the rocks and trees, of running water and everything alive was the bond between us. This trip to the Little Bighorn was before the time of entrance fees, crowds of visitors, and centers where hundreds of books are for sale that explain both sides of “what-ever” happened. We stood safe that morning in weathered stems of bear grass that poked skyward from lush, green clumps scattered across broken rock. The river below twisted a pattern into the prairie soil and disappeared into some unknown place and distance that we could only speculate upon.

“Eagle!” She pointed to the large bird gliding above the river.

“Nice,” I whispered.

We watched in silence until the eagle faded from our sight.

“Ready?” I readjusted my pack.

“Do they have eagles in Canada?”

“Let’s go,” and I stepped back on the trail. “I think so.”

Much later I would admit to an unspoken uneasiness as we walked the narrow path up to the crest of the ridge. The air had that feel of rain and there was a darkness on the far horizon. Light puffs of wind meandered across the upper slope and the wiry shoots of prairie grass gently leaned in unison toward our hilltop position. The sweet smell of spring bloom and the smoke from a small campfire settled into the safety of the cottonwoods along the river bottom. A few song sparrows, silent and with no discernable flight pattern, crossed high above. Surely, those distant clouds would veer off and pose no real threat to our trip.

“You sure about this group we are hooking up with?”

“They know what they are doing.”

“And crossing the border and the job thing?”

“What choice have we got?”

“I hate this.”

“It’ll work out. You worry too much.”

“Or welcome to Vietnam!”

But the storm did not track north. It turned and bore straight on. Within minutes, wave after wave of cold air blew from the darkened base of the towering cloud and jagged daggers of lightening stabbed into the folds of a distant hill. A discarded shopping bag burst from the grass, tumbled across the trail and caught on a lower rail of the metal enclosure. The tattered ends of the empty plastic rattled a song of angry protest.

With each boom, the sound turned more intense, more focused and the black iron fence that surrounded the gravestones could not slow the darkness that chased the last color from the sky. The clusters of stone markers scattered across the hillside momentarily glowed with each flash of lightening.

I looked back and did not realize how far she had fallen behind. I

backtracked to the ledge where she was sitting.

“What’s up?”

“I need some moleskin.” She had removed her left boot.

“Hurt much?” I dropped my pack and rummaged for the first-aid kit.

“It’s these new boots! I should have taken the old ones.”

“Guess we’re really in for it,” I mumbled as a spider web of danger sparked horizontally across the sky. I counted the seconds before the thunder rolled to our perch high above the Little Bighorn River. “Ten seconds.” I looked from my wristwatch back to the cloud. “About two miles away.” I turned up my collar to the wind and moved around the corner of the iron fence. From this new angle, I resampled the light reading on the camera, slowed the shutter speed and focused on the stone marker.

“G. A. Custer, 7th U.S. Cav. June 25 1876”

I had time for two quick shots with my old camera before the first heavy drops of rain chased us back to the car and the winding road to another place.

The sheets of heavy rain made it hard to distinguish the gravel surface from the ditches on either side. We both focused through the speeding wipers as they cleared semi-circles across the windshield and I wondered if we had allowed enough time to make our appointment.

“Pull over! You need to stop so I can clear the streaks on the window.”

I tapped the brakes and checked the rearview mirror. “It would be nice to

get out of these wet clothes.”